|

Francis Fukuyama may yet prove to be right in predicting the

end of history. But there is no doubt that he was premature. The

idea that people have reached an "end point" of "ideological evolution

and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form

of human government" quite obviously seems out-of-step with our

political reality in 2018. It could still happen one day. But it surely

hasn't happened yet.

Fukuyama knows this. However, to ensure that this is only a temporary

setback — not a permanent blow — for his thesis, he has penned Identity:

The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment.

Collapse of Soviet communism, Western liberal democracy and the free

market had triumphed and history had reached its "end" — Humans had

finally formed a political organization in harmony with their inner

nature. Though nations still on the other side of history could

certainly cause trouble for liberal democracies, they could not offer a

serious alternative.

America and populist

right wing "dietarian" movements all around Europe have jolted Fukuyama

out of his Hegelian certitude. And so he has hurriedly written Identity:

The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment, a book

that goes back to the beginning of Western thought and retraces its

evolution to see where it took a wrong turn.

What emerges from it, however, is not a

new way forward but an old and beaten path of income redistribution and

a national unity program. Basically, Fukuyama's solution is to redirect

the ethnic identity politics of the left and the right into a renewed

"creedal identity" that satisfies the natural human need for dignity and

recognition that Hegel said was the main driver of history. Such a Big

Government roadmap will actually work or make matters worse.

Hegel postulated that as human consciousness evolved so would human

institutions or social organizations until all the internal

contradictions of the psyche were resolved in a final rational polity.

Hunter-gathering and tribal societies developed into slave-owning ones

that morphed into monarchies or theocracies that finally modernized into

liberal democratic polities.

So why are liberal democracies in trouble? Because, notes Fukuyama, they

have ignored a core psychic need.

Plato and other ancient Greek philosophers believed that thymus, or

pride, was as essential as desire and reason.

And it craved satisfaction just like the others. But they also believed

that this part was in tension with itself. On the one hand, individuals

wanted equal recognition of the fundamental worth or inner dignity of

human beings (isthmian). On the other hand, they also wanted

to be recognized as better than everyone else (megalothymia).

Megalothymia results in constant jockeying for power and domination

in every facet of human life, especially politics.

Hegel's great insight was that recognition achieved through domination

is self-defeating because people crave the recognition not of their

inferiors (slaves) but superiors (masters). The minute they succeed in

dominating someone, that person's recognition becomes worthless. The

quest for recognition can thus only be satisfied in a society of equals.

For Hegel, the quest for dignity and recognition — or identity politics,

in our parlance — has been the ultimate driver of history, and will end

in an egalitarian liberal democracy with a commitment to individual

rights and justice.

Two developments have prevented liberal democracies from delivering on

Hegel's utopia, as Fukuyama explains.

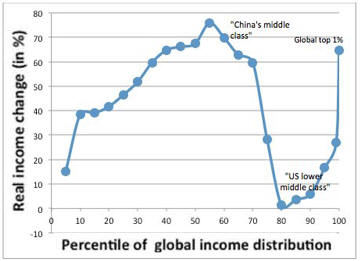

First, the rise of income inequality. Thanks to globalization and

productivity growth between 1988 and 2008, the world has become

immensely richer. However, the lion's share has gone into the pockets of

the rich, hollowing out the middle class. Fukuyama does not claim that

this growth has necessarily hurt anyone. To the contrary, he admits that

those in the 20th to 70th percentile experienced bigger income increases

than those in the 95th. However, the global population around the 80th

percentile — which corresponds with the working middle class in the West

— experienced only marginal gains. These trends were most pronounced in

Britain and the United States, the two countries at the forefront of the

"neoliberal revolution" that Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan

spearheaded.

Middle-class stagnation, in Fukuyama's telling, is more problematic from

a thymotic standpoint than an economic standpoint because the

real purpose of income, once you reach a certain point at least, isn't

to feed material needs but positional ones. So even if the middle class

in the West has suffered no absolute loss of income, the relative loss

of status makes these people feel ignored and invisible.

The other factor is the rise of the wrong kind of dignity or identity

politics.

Some identity politics seek to honor the inner "dignity" of individuals

by extending basic state protections to all citizens irrespective of

race, caste, creed, or religion. This is noble, but in practice has

transmogrified into a "therapeutic state" whose main aim became to

rescue what the French philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau called the

innate "goodness of man" from the corrupting demands and conventions of

society. Self-actualization rather than social cohesion became the

political project. As but one example: California formed a task force to

"Promote Self-Esteem and Personal Social Responsibility." The 1990

manifesto could have been plucked out of the Esalen

Institute. (Sample statement: "The point is not to become acceptable

and worthy, but to acknowledge the worthiness that already exists.")

This type of identity politics has uncorked personal pathologies that

religion had kept in check, particularly an unquenchable narcissism that

social critic Christopher Lasch famously called out because it sought

external social validation from the very society it constantly

undermined.

Another kind of identity politics seeks the dignity of "collectives,"

essentially rejecting the idea of some generic inner dignity of

individuals while disrespecting the sense that their particular racial,

cultural, religious, linguistic, and other connections could satisfy

the thymotic needs of marginalized groups. Fukuyama

acknowledges that this sort of identity politics has done some good.

After all, blacks couldn't launch their struggle to end the atrocities

of the Jim Crow era without building black pride. Similarly, women

couldn't dislodge engrained social "discrimination, prejudice,

disrespect, and simple invisibility" without a feminist movement that

celebrated womanhood.

But the advent of multiculturalism took things too far, Fukuyama

believes. It encouraged an ever-proliferating panoply of

micro-identities to seek not equal treatment from society but separation

from it because, ostensibly, each group's "lived experience" of

victimization — another concept borrowed from Rousseau, Fukuyama points

out — was different and inaccessible to outsiders. Multiculturalism

built silos instead of bridges with broader society.

Multiculturalism also prodded the left to abandon its traditional

emphasis on economic inequality precisely when the dignity and status of

the Western middle class was taking a beating from globalization. This

left many ordinary people without a political home to voice their

insecurities, paving the way for right-wing demagogues to launch their

own brand of reactionary blood-and-soil identity politics — using the

language and tactics of their leftist fellow travelers.

"That the demand for dignity should somehow disappear is neither

possible nor desirable," notes Fukuyama.

This is a charmingly old-fashioned idea. There is much to like about it.

But the Big Government roadmap that Fukuyama lays out is problematic to

say the least.

Fukuyama admits that he has no use for limited government libertarianism

and, in fact, believes that it was unfortunate that the right's critique

of the unintended consequences of ambitious social programs unnerved the

left. It's high time, he thinks, to stop being shy about using

government to achieve national unity.

The Netherlands, for example, must end its age-old acceptance of "polarization,"

or letting different religious groups establish their own schools,

newspapers, and political parties. It was one thing to go along with

this arrangement when it meant buying social peace among Catholics,

Protestants, and secularists. But it has ghettoized Muslim immigrants

and prevented them from assimilating, claims Fukuyama.

This sounds good on its face. But America's relatively limited

experiment with state-enforced busing to end segregation was a disaster.

White families who didn't want their children to have to spend hours

being transported to another school district put their kids in private

or parochial schools or fled from inner cities to distant suburbs

outside of the busing zone. All of this exacerbated segregation and

racial tensions. But Fukuyama seems so determined to ignore the danger

of unintended consequences that he doesn't entertain any downside to his

proposal, much less question its feasibility.

In America, Fukuyama believes, the left needs to return to a class-based

politics that unites various marginalized groups around pocketbook

concerns. At the electoral level that means that Democrats should quit

playing identity politics and nominate a younger version of Joe Biden

who can connect with the working class, regardless of race, sex, or

religion. At the programmatic level, it means a renewed embrace of

redistribution programs on the scale of the New Deal and the Great

Society. He also wants a "national service" program that replicates the

military's stellar success in assimilating recruits of diverse

backgrounds.

The primary point of returning to a redistributive politics is not so

much to expand the social safety net as to even out envy-inducing social

hierarchies. In other words, make the rich poorer and the poor richer to

make the working class feel better about itself. That such policies

would be fiscally unaffordable and economically deleterious, Fukuyama

doesn't consider. But the bigger problem from his own standpoint is that

giving government more control over more wealth is likely to deepen

existing social fissures by triggering a fiercer race for the spoils,

especially in the post-Trump era where whites are emboldened.

Fukuyama's call for national service is perhaps more innocuous, but it's

hard to see how it'll accomplish much. The military is united around a

clear mission — protecting the nation — that helps overcome other

divides. What would be the unifying passion of national service? Digging

sewers in poor neighborhoods might appeal to congenital do-gooders but

it's not the kind of thing that brings people together like the enemy at

the gate.

What's befuddling about Fukuyama's recommended agenda is that it

ultimately departs from his own Hegelianism. Hegel, contra Marx,

believed that ideas shaped the material — economic — world, not vice

versa. That means that the political battle is ultimately an ideological

battle. Victory depends on winning hearts and minds, not economic

appeasement. If that's the case, Fukuyama would have been better off

exposing what's false, contradictory, and self-negating about the new

and pernicious identity politics of the left and right and leaving it at

that.

Nevertheless, Fukuyama has written an intricate account of this peculiar

phenomenon. It is a must-read for anyone interested in understanding our

bewildering political times in a broader historical and philosophical

context.

What's needed now is a renewed commitment to "e

pluribus Unum,"

Fukuyama says.

|

v

v