|

VI. Has Helping the Unemployed

Worked

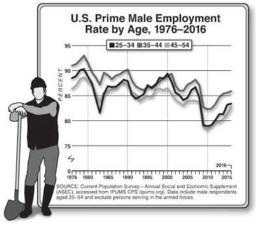

The War on Work—and How to End It

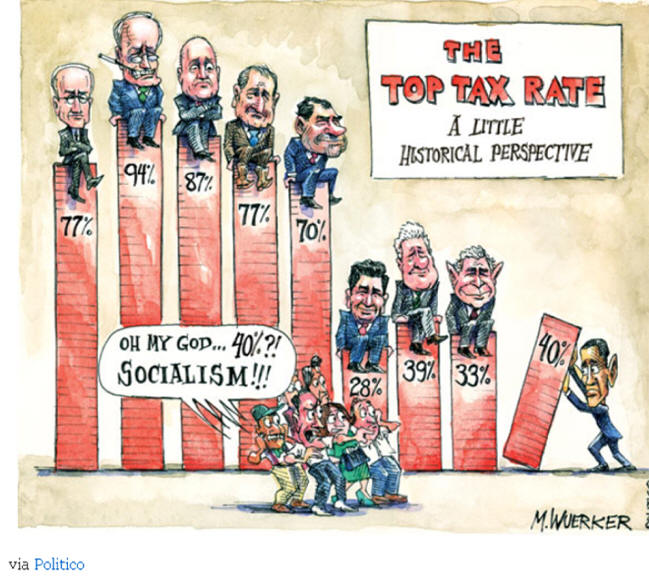

"Unfortunately, policymakers seem intent on making the joblessness

crisis worse. The past decade or so has seen a resurgent progressive

focus on inequality—and little concern among progressives about the

downsides of discouraging work. Advocates of a $15 minimum hourly wage,

for example, don’t seem to mind, or believe, that such policies deter firms

from hiring less skilled workers. The University of California–San Diego’s

Jeffrey Clemens examined states where higher federal minimum wages raised

the effective state-level minimum wage during the last decade. He found that

the higher minimum “reduced employment among individuals ages 16 to 30 with

less than a high school education by 5.6 percentage points,” which accounted

for “43 percent of the sustained, 13 percentage point decline in this skill

group’s employment rate.”

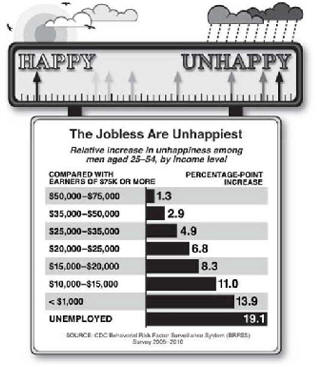

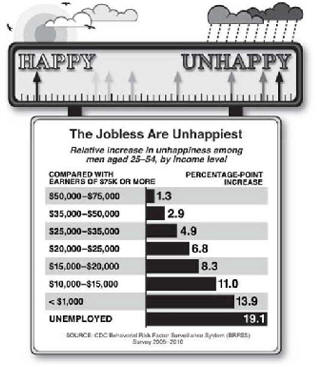

The decision to prioritize equality over employment is particularly

puzzling, given that social scientists have repeatedly found that

unemployment is the greater evil. Economists Andrew Clark and Andrew Oswald

have documented the huge drop in happiness associated with unemployment—about

ten times larger than that associated with a reduction in earnings from the

$50,000–$75,000 range to the $35,000–$50,000 bracket. One recent study

estimated that unemployment leads to 45,000 suicides worldwide annually.

Jobless husbands have a 50 percent higher divorce rate than employed

husbands. The impact of lower income on suicide and divorce is much

smaller. The negative effects of unemployment are magnified because it

so often becomes a semipermanent state. repeatedly found that

unemployment is the greater evil. Economists Andrew Clark and Andrew Oswald

have documented the huge drop in happiness associated with unemployment—about

ten times larger than that associated with a reduction in earnings from the

$50,000–$75,000 range to the $35,000–$50,000 bracket. One recent study

estimated that unemployment leads to 45,000 suicides worldwide annually.

Jobless husbands have a 50 percent higher divorce rate than employed

husbands. The impact of lower income on suicide and divorce is much

smaller. The negative effects of unemployment are magnified because it

so often becomes a semipermanent state.

Time-use studies help us understand why the unemployed are so miserable.

Jobless men don’t do a lot more socializing; they don’t spend much more time

with their kids. They do spend

an extra 100 minutes daily watching television, and they sleep more. The

jobless also are more likely to use illegal drugs. While fewer than 10

percent of full-time workers have used an illegal substance in any given

week, 18 percent of the unemployed have done drugs in the last seven days,

according to a 2013 study by Alejandro Badel and Brian Greaney.

Joblessness and disability are also particularly associated with America’s

deadly opioid epidemic.David Cutler and I examined the rise

in opioid deaths between 1992 and 2012. The strongest correlate of those

deaths is the share of the population on disability. That connection

suggests a combination of the direct influence of being disabled, which

generates a demand for painkillers; the availability of the drugs through

the health-care system; and the psychological misery of having no economic

future.

Increasing the benefits received by nonemployed persons may make their

lives easier in a material sense but won’t help reattach them to the labor

force. It won’t give them the sense of pride that comes from economic

independence. It won’t give them the reassuring social interactions that

come from workplace relationships. When societies sacrifice employment for a

notion of income equality, they make the wrong choice.

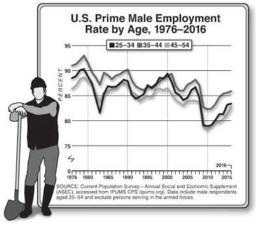

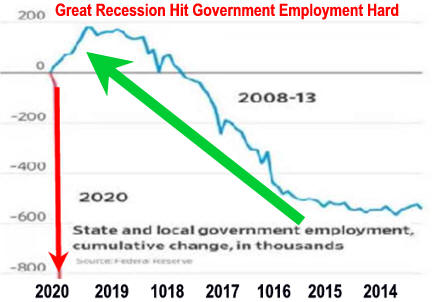

Politicians, when they do focus on long-term unemployment, too often

advance poorly targeted solutions, such as faster growth, more

infrastructure investment, and less trade. More robust GDP growth is

always a worthy aim, but it seems unlikely to get the chronically jobless

back to work. The booms of the 1990s and early 2000s never came close to

restoring the high employment rates last seen in the 1970s. Between 1976 and

2015, Nevada’s GDP grew the most and Michigan’s GDP grew the least among

American states. Yet the two states had almost identical rises in the share

of jobless prime-age men.

Infrastructure spending similarly seems poorly targeted to ease the problem.

Contemporary infrastructure projects rely on skilled workers, typically with

wages exceeding $25 per hour; most of today’s jobless lack such skills.

Further, the current employment in highway, street, and bridge construction

in the U.S. is only 316,000. Even if this number rose by 50 percent, it

would still mean only a small reduction in the millions of jobless

Americans. And the nation needs infrastructure most in areas with the

highest population density; joblessness is most common outside metropolitan

America. (See “If You Build It . . .,” Summer 2016.)

Finally, while it’s possible that the rise of American joblessness would

have been slower if the U.S. had weaker trade ties to lower-wage countries

like Mexico and China, American manufacturers have already adapted to a

globalized world by mechanizing and outsourcing. We have little reason

to be confident that restrictions on trade would bring the old jobs back.

Trade wars would have an economic price, too. American exporters would cut

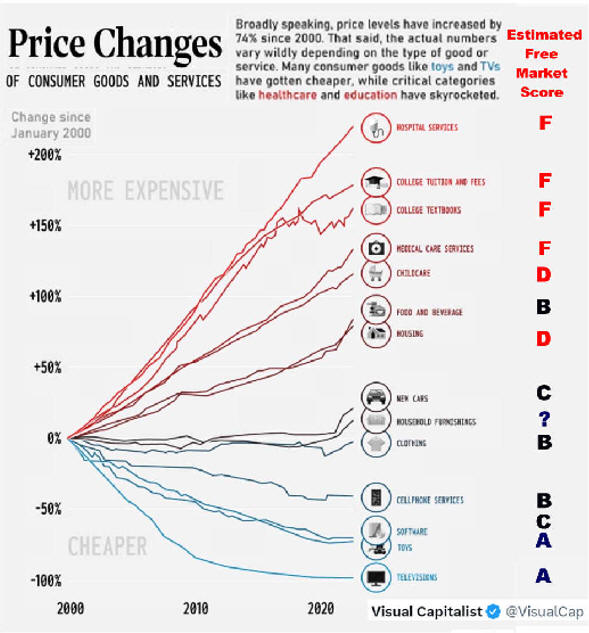

back hiring. The cost of imported manufactured goods would rise, and U.S.

consumers would pay more, in exchange for—at best—uncertain employment

gains.

The techno-futurist narrative holds that machines will displace most

workers, eventually. Social peace will be maintained only if the armies of

the jobless are kept quiet with generous universal-income payments. This

vision recalls John Maynard Keynes’s 1930 essay “Economic Possibilities for

Our Grandchildren,” which predicts a future world of leisure, in which his

grandchildren would be able to satisfy their basic needs with a few hours of

labor and then spend the rest of their waking hours edifying themselves with

culture and fun.

But for many of us, technological progress has led to longer work hours, not

playtime. Entrepreneurs conjured more products that generated more earnings.

Almost no Americans today would be happy with the lifestyle of their

ancestors in 1930. For many, work also became not only more remunerative but

more interesting. No Pennsylvania miner was likely to show up for extra

hours (without extra pay) voluntarily. Google employees do it all the time.

Joblessness is not foreordained, because entrepreneurs can always dream

up new ways of making labor productive. Ten years ago, millions of

Americans wanted inexpensive car service. Uber showed how underemployed

workers could earn something providing that service. Prosperous, time-short

Americans are desperate for a host of other services—they want not only

drivers but also cooks for their dinners and nurses for their elderly

parents and much more. There is no shortage of demand for the right kinds of

labor, and entrepreneurial insight could multiply the number of new tasks

that could be performed by the currently out-of-work. Yet over the last

30 years, entrepreneurial talent has focused far more on delivering new

tools for the skilled than on employment for the unlucky. Whereas Henry

Ford employed hundreds of thousands of Americans without college degrees,

Mark Zuckerberg primarily hires highly educated programmers." Unnfortunately, policymakers seem intent on making the

joblessness crisis worse.

Little concern among progressives about the downsides of discouraging

work.

Jeffrey Clemens increase state-level minimum wage during the last decade.

“reduced employment among individuals ages 16 to 30 with less than

a high school education by 5.6 percentage points,” which accounted for

“43 percent of the sustained, 13 percentage point decline in this skill

group’s employment rate.”

"huge drop in happiness associated with

unemployment—about ten times larger than that associated with a reduction in

earnings from the $50,000–$75,000 range to the $35,000–$50,000 bracket.

One recent

study estimated that unemployment leads to 45,000 suicides worldwide

annually. Jobless husbands have a 50 percent higher divorce rate than

employed husbands. The impact of lower income on suicide and divorce is much

smaller. The negative effects of unemployment are magnified because it so

often becomes a semipermanent state."

Increasing the benefits received by nonemployed

persons may make their lives easier in a material sense but won’t help

reattach them to the labor force Joblessness and disability are also

particularly associated with America’s deadly opioid epidemic. |

repeatedly found that

unemployment is the greater evil. Economists Andrew Clark and Andrew Oswald

have documented the huge drop in happiness associated with unemployment—about

ten times larger than that associated with a reduction in earnings from the

$50,000–$75,000 range to the $35,000–$50,000 bracket. One recent study

estimated that unemployment leads to 45,000 suicides worldwide annually.

Jobless husbands have a 50 percent higher divorce rate than employed

husbands. The impact of lower income on suicide and divorce is much

smaller. The negative effects of unemployment are magnified because it

so often becomes a semipermanent state.

repeatedly found that

unemployment is the greater evil. Economists Andrew Clark and Andrew Oswald

have documented the huge drop in happiness associated with unemployment—about

ten times larger than that associated with a reduction in earnings from the

$50,000–$75,000 range to the $35,000–$50,000 bracket. One recent study

estimated that unemployment leads to 45,000 suicides worldwide annually.

Jobless husbands have a 50 percent higher divorce rate than employed

husbands. The impact of lower income on suicide and divorce is much

smaller. The negative effects of unemployment are magnified because it

so often becomes a semipermanent state.